It's been a little over a month since our daughter came home from the hospital, and in that time our lives have very much returned to normal. We've received many words of encouragement from the hundreds of family members and friends who have followed our daughter's progress via this blog, and we appreciate them tremendously. It seems appropriate to give a final update and record a few thoughts to complete this history of what has become a defining chapter in the life of our family.

Today our daughter had a follow-up visit with her neurologist. He performed a standard neurological assessment and found no impairment. He was curious about the precise findings from our visit to Stanford last month and asked that we have a report sent to him. We learned that one of the genetic tests on our daughter's blood is still outstanding at a specialized university lab in another state, and the neurologist promised to follow up with us once he has received the final result. This test seems like more of a formality than anything, as there is nothing in our daughter's condition that would indicate the presence of an underlying disease or genetic condition that could have led to her stroke.

The neurologist's clinic is located on the campus of the children's hospital, so after her appointment our daughter enjoyed lunch in the cafeteria. After all the time she has spent in the hospital she doesn't seem to mind going there as much as my wife and I do. In fact, she has said to us on several occasions during the past few weeks: "The hospital is much more fun than our house!" We're grateful that she doesn't seem to have any unpleasant memories or lingering fears of the hospital as a result of her stay.

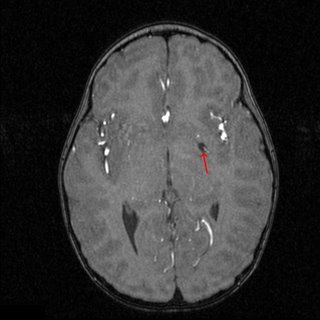

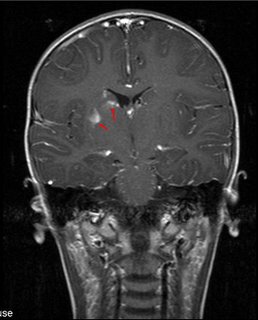

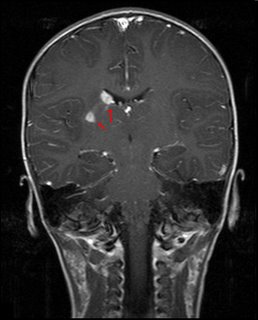

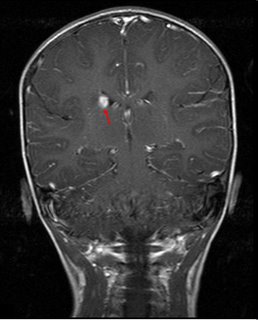

As my wife and daughter were in line at the cafeteria they happened to run into the head pediatric resident who took care of our daughter during her first night in the PICU at the trauma hospital. She had taken a special interest in our daughter throughout her stay, and my wife and I appreciated the fact that she went above and beyond to keep us informed and keep our daughter comfortable. I was surprised to learn that the doctor remembered our daughter's name and so much detail about her case even after six weeks and countless other sick children. "What did those other two spots in her brain turn out to be?" she asked. My wife filled her in on the details of the diagnosis.

After lunch our daughter got to make a quick visit to the gym in the Rehab unit to visit her physical therapist, who along with the aforementioned head resident and another nurse from the trauma hospital are in our daughter's "hall of fame" as her favorite caregivers. I'm sure our daughter enjoyed showing her therapist all of the things she has been able to do over the past six weeks.

Her physical recovery is all but complete. She runs, she jumps, she swims better now than she did before her stroke. She walks on the balance beam in her gymnastics class. She rides her bike, although with the training wheels back on for now, but they will come off again soon enough. She can hop on her left foot, although with less confidence and fewer repetitions than on her right. She plays the piano with both hands and continues to learn new songs every week. She has learned to play a few simple songs on her new violin and is always eager to practice. She's enrolled in a ceramics class and recently finished painting a clay figurine of a mouse that my wife made for her. She's back on schedule with her studies and will finish her kindergarten math, phonics, reading, and writing this week.

Our daughter seems to be internalizing and coping with what has happened to her mentally and emotionally. She plays with her stethescope and other medical toys from time to time, usually practicing on her stuffed animals but occasionally on her friends. The other day she put her anesthesia mask on a friend and pretended to put him into an MRI machine (under a desk). She talks about her experience with just about anyone who will listen, including total strangers. While we were on our flight to Stanford last month I returned from the restroom to find her chatting with the woman sitting next to her about her stroke. The other day, my wife and daughter were in a Hallmark store when our daughter approached the clerk (a woman in her 60s), started up a conversation, and soon said:

"Do you know that I had a stroke?" our daughter asked matter-of-factly.

"Really?" the woman replied, a bit surprised. "So did I, about five years ago! I couldn't move my right side at all."

"Well I couldn't move my left side!" our daughter exclaimed excitedly.

They continued talking for a while. My wife reported that the experience was amazing to witness. There seemed to be an instant bond between these two based on their similar experiences, in spite of the 60 years that separated them age-wise.

Our daughter also has many, many, many questions about what happened to her. We try to answer them as best we can. If nothing else, this experience seems to have taught her that there is an answer to almost anything having to do with illness or injury of the human body. As if any four-year-old needed extra incentive to ask more questions! We welcome the chance to teach her about this experience and hope that in so doing we will help her to continue to cope with it.

Our two-year-old son isn't about to be left out of the excitement of all this new-found knowledge. A couple of weeks ago he announced to his nursery class at church that his sister "fell out of a swing and got a scratch on her brain and had a stroke." It was interesting to hear that sequence of events expressed in his own words, he seems to understand as much as anyone can expect of a child his age.

My wife and I, allegedly the mature adults of the bunch, are also still struggling somewhat to process what has happened to our family. Part of each of us seems eager to forget the experience and part seems determined to always remember it. Every few days I catch myself running through the instant replay of the first full day in the PICU when we first glimpsed the breadth and depth of what we were dealing with, and sometimes I still struggle to maintain my composure as I relive the experience in my mind. I'm not sure if it's from gratitude for our present blessings or from a fleeting memory of the pain we experienced in the past, but my own emotions about this experience are still a bit raw.

Given the choice between gratitude and all else, we choose to focus on gratitude. Our hearts are full of thanksgiving for our prayers and those of so many friends and family members having been heard and answered. We're extraordinarily grateful for what we've experienced as a family, we can see how it has drawn us closer together and helped us to appreciate each other more. It may seem easy for us to feel this way given such a good outcome, but we truly struggle to understand why we have been so blessed. We did nothing to merit this blessing, but it was given to us nonetheless. The mechanics of this situation cannot be rationalized. It is as futile to attempt to reconcile the good fortune of our daughter's recovery with some merit on our part as it is to attribute the misfortune of her accident to some misstep.

Instead, we trust that all things have been done in the wisdom of Him who knoweth all things. We rejoice, we give thanks, and we continue to pray for greater understanding so that we might appreciate these blessings even more.